One of the first memories I have is of standing in the dark, in the basement, inside a tiny walled off darkroom, next to my mother. The only light was from an enlarger as it illuminated the easel below it. I could see an image appear in negative under the light. I tried to recognize what it was. It appeared to be faces, but I didn’t know who the people were. They looked like smooth gray stone carvings while the sky behind them was eerily black. In the silence, my mother turned a knob to focus the image against the white of the easel, then she adjusted the easel to line it up so the image wouldn’t be crooked. She fussed with the crop, lowered the enlarger slightly, then turned it off.

All the light that remained was the dim glow of a red safety lamp as she continued on. My eyes slowly adjusted. I could barely see my mother reach into a box marked KODAK containing a thick black plastic sleeve. She removed a small piece of paper. She was careful to tuck the end of the sleeve down and close the box when she was done. I wasn’t sure why she did that.

She placed the paper under the easel frame and lowered the criss-crossing metal bands to hold it in place. She flicked the enlarger light back on. This time it buzzed for a moment, then shut off automatically. She removed the paper, then placed it into a nearby tray filled with acrid smelling clear fluid. She rocked the pan gently, back and forth, using rubber-tipped bamboo tongs to push the curly corners of the thick paper under the fluid, evenly coating every inch of it.

What I saw next was magical. I was transfixed, staring at the blank paper as it shimmered, very slowly an image began to emerge upon its surface. What had looked so alien to me just moments ago was beginning to reveal a familiar scene. Faces appeared. It was our family, but in grayscale. My father and mother stood squinting slightly in the bright sunshine, protectively flanking my brother and I. We were standing in our back yard near the plot of blooming sunflowers my mother had planted that spring. It was daytime, not night. We all had smiles plastered on our faces. You always had to smile for the camera, right? So we did. We were the most perfect American family, smiling away.

But we really weren’t.

—————————–

Photography is in m DNA. My grandfather operated movie projectors in theaters in New York City in the 1930s. My uncle Bill took up photography when he was stationed in Germany during WWII. When he came back to the United States, he gave my mother one of his old Argus cameras. Perhaps it was just having a camera and having little kids that drew my mother to learning about photography. It wasn’t simply point-and-shoot back then. You had to understand F-stop, shutter speed, film speed, film types, paper types, chemicals and more. Since my mother was a scientist (and probably a genius or at least had a very high IQ) I don’t think she struggled much with learning the ropes.

Memories of my childhood always include my mother with a camera either around her neck on a big leather strap or with her old Yashika twin lens reflex carefully balanced in her hand.

I was constantly told to “go stand on that cliff edge or by the stream or near the TV showing flickering images of the moon landing.” Or “form a group” (when company came to visit) or “stand up straight and suck in, chin up.” I did what I was told, at first, but over the years I began to deeply dread the intrusion of the ever-present camera watching my every move. It was as if there was a fifth person in our family, an annoying person, who was always in our business, and I mean always.

My mother documented anything and everything from a shockingly large bowel movement my brother took, to me moments after I had spread Lassar paste and talcum powder onto her newly created woven art panels, instead of taking a nap, to our cat Yukio’s lifeless body surrounded by candles after he died, to my dad recovering from surgery in his hospital bed. Today we think nothing of this intrusion. In fact, we embrace being on camera. We show off how fabulous our life is through our carefully retouched images—but this was in the 1960s. There was no social media or even computers. Only our neighbors had color TV.

I don’t know why my mother was such a rabid documenter of all things. I have a hunch she used it as a way to control situations. She could walk into a place where maybe she didn’t belong, but she had a camera, a commanding tone, and confidence so no one got in her way. We had to listen to her. We had to form that group. We had to look happy when we weren’t. We had to create her vision of whatever she thought we were supposed to be.

She’d spend evenings creating photo albums after she printed out the best images. She’d clip out newspaper articles or save birthday cards or other bits she could add to each page. She not only wrote captions for each photo, but she told a story or wrote something funny. She carefully labeled and organized each and every roll of processed film. She did scrapbooking before it was a thing-40 years ahead of her time.

Then, of course, she would debut the album and we’d all look and point at ourselves and squawk about how bad we looked or we’d laugh at each other or what she’d written. Over the years we’d use the albums to settle disagreements about something that happened. Mother had documented it so we had proof. To settle an argument meant simply running upstairs into the spare bedroom, scan the collection of albums, organized by year, and choose the one that would decide who was right and who was wrong.

When it was a dull, snow day, we’d grab a few albums and reminisce as we looked over the pages. We’d see how much we changed, growing so tall or so fat or so old…they truly were a detailed timeline of our lives.

Eventually, cameras felt like a natural extension of my body, too, since I was often the one taking the photo when my mother needed to be in the shot. By the time I left for college I was making images, not forming groups or trying to document things. I was far more interested in how my ability to see things changed when viewed through a camera lens. I could photograph droplets of water as they left the garden spigot, but before they landed on the ground. I literally froze time, then could take time to examine the nuances in a moment that would otherwise go unnoticed. It was fascinating.

I could tell a story through images.

I attended the Minneapolis College of Art & Design, where I majored in photography. I wasn’t certain what I’d do with that degree, but creating images was my passion. By the time I graduated, I was developing color slides, 20” x 24” color prints, I had gallery shows at the college and I was one of the senior staff photographers. I was making studies in light and shadow, of form and shape. I eventually realized I wanted to do more than be a fine art photographer because I loved to write and I loved typography so I studied graphic design.

I still have a bag full of cameras and lenses, and heart filled with the joy of having a career as a creative director, and I have my mother to thank for some of that.

———————-

In 2006 my mother died. It was unexpected. She’d hidden how sick she really was so when I drove to her house to check on her, it was a terrible blow to find her on the floor in the living room, already gone. Photography was so ingrained in me I was tempted, for a moment, to take a photo of her lifeless body, still dressed for work in a turquoise blue cotton shirt and white pants. But I quickly realized that even though she would have wanted it, I was not the kind of person to do that kind of thing. I felt repulsed that I even considered it.

As the Executrix of my mother’s Estate. It was my job to figure out what to do with all those photo albums…all 140 of them…and all the carefully marked shoeboxes of negatives…and some slides…some super 8mm movies…

I didn’t have space to store the albums and negatives, so my brother and I agreed that since he had the space, he would take them. I would take the slides and other media since it was rather limited. I’d be able to come visit or borrow an album so I could scan a few photos. All those times I was annoyed, I didn’t want to be photographed, and here I was feeling awful that I wouldn’t be able to see those images again so easily. Most of my life was documented on those pages and those of the rest of my family, many whom are long gone.

The albums are a precious archive of our little family. Maybe those fake smiles weren’t so fake? Maybe I could now start to believe the vision my mother had of her family after all?

But it didn’t work out that way.

————————

My brother and I are on the outs. We never really got along very well to begin with. There was either a battle for our parents affection or a battle with each other. As an adult it mellowed into a somewhat friendly relationship, but it was never as close as I wished it could have been. Even with my mother begging us to always get along and always be a part of each other’s lives, it just didn’t happen. I didn’t even see my brother for 10 years after my mother died, and he lives only a few miles away.

And then, on my birthday in 2018, my brother shows up at my door with his second wife. I was completely stunned and began crying, not sure if he was there to shoot me or hug me. I wrote about it HERE, but the short version is, he was there to tell me he got his DNA report done. It showed something none of us expected-we’re not FULL SIBLINGS. He’s my half-brother.

I was devastated; rage consuming me about my mother with no way to say anything to her about it. I’d been completely betrayed by her. How could she not tell us? How could she see us not getting along and not say a word? My father was long gone. He would never find out, so what was she risking by not telling us after he died? Was she so worried about her phony family image that she forced us to look like a solid unit when we weren’t? Nearly two years after finding out the truth about my brother, I am still unable to process this nightmare. It makes me feel like my life is a lie.

In my heart, I wished for a close relationship with my brother. He’s just about all I have of a family, but now even what little I might have had is cut in half.

But what about the photo albums? Maybe I shouldn’t even care any more.

I’ve tried to let go of needing to see these images. I do have memories and no one can take that away from me. I want to convince myself that’s all I need, but then I recently heard the news that my brother moved away. He and his second wife are selling their house in Connecticut. He didn’t even tell me. What is going to happen with all the photos?

Why do I even care?

—————————–

Being able to see the photos ignites memories that have slipped into the dark recesses of my mind. I am haunted by what has recently been revealed about my family. Perhaps there are clues in the images if I look hard enough.

I fear it will also hurt, maybe even break me, to see those images. Is it a documentation of betrayal and lies or are there kernels of the “real” family there to discover, too?

But I can’t see the photos. Maybe ever again. My brother moved away without a word. Before I knew this, I contacted a company that specializes in scanning photos and film. Just to scan the pages of the photo albums, not each photo, would be nearly $15,000. I knew it would be expensive, but that’s a deal breaker for me. It doesn’t include scanning the film or negatives either.

I’m trying to let go of this need to reconnect with my past. I have a very few photos from my childhood. Maybe that’s enough. I can’t fix what’s broken in my family. I have to let go.

Then, a few months ago, my nephew came over. We were going out for dinner, but first he had to bring something into the house for me from my brother. He gave me two HUGE cardboard boxes that contained plastic shoe boxes. Inside each shoe box were a handful of paper envelopes. Inside each envelope were film negatives. ALL the negatives from ALL of the photo albums were in those big boxes. At first, my heart sank. What would I do with negatives? Thankfully after a quick check, they appeared to be in good shape, but how could I ever see the images again?

The boxes sat in my dining room until a few days ago. I knew I couldn’t afford to have the negatives scanned. It would be just as costly to do so, when in truth, I wouldn’t even want every negative scanned because there were plenty of images that were under or over exposed, or just not great photos. The best were printed out and used in the albums, but I have no idea which negatives should be scanned.

Sam and I rented two storage spaces. One was for the contents of his mom’s apartment and one was for our things. We were just about to take the boxes to the storeroom when I had an idea. I have a scanner, but it’s only for paper-or so I thought. I wondered if I could scan the negatives. I figured I’d try before we sealed the boxes and put them away.

I chose a shoe box marked 1966. Inside the first envelope, marked November 1966, were holiday portraits of my family. I couldn’t see much detail but the negatives were large, 120mm. Some were color and some black and white. I opened the lid of the scanner and discovered there was a board on the inside cover. I removed it to reveal a second light source. That way the scanner could scan a negative. I was so excited I couldn’t move fast enough to give it a try.

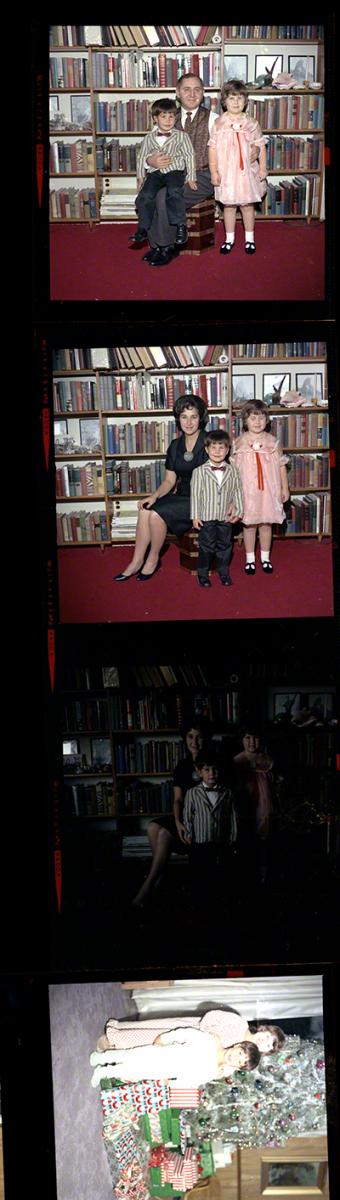

©1966 Feminella Family. The first scan, quickly color corrected.

I didn’t worry about dusting off the scanner or the negative. I desperately wanted to see the images. I set the software to scan at a very high resolution and let it rip. It took a few minutes, then suddenly the image opened in photoshop. What I didn’t know is the scanner converted the negative into a positive. Right before my eyes there appeared a portrait of me, my brother and my dad in our holiday finest. There was some damage to the film and in one exposure my eyes are closed. I didn’t care. I was transported back in time as I looked at the images. I remembered wearing that dress. We went on a trip to the United Nations and I wore that dress. It was very stiff fabric and scratched at my skin. The shoes were too tight. I don’t remember many outfits over the years, but that one really stuck in my head.

My hair was cut short. I looked like I might have a mental disability because my eyes were slightly crossed (later fixed by surgery). I wasn’t thrilled seeing that, but what I did love was seeing my daddy. He looked tired, maybe resigned to his life. Maybe just tired from being around little kids. He had a good grip on us, probably because my little brother would have run off if he didn’t have a firm hand on his waist. My father was wearing his wedding ring. He stopped wearing it in the 1970s after he had an accident in the garage and cut his fingers. He could have worn the ring once he healed, but he didn’t. My mother didn’t wear hers, either. She’s not wearing one in the photo.

I wear my dad’s ring now, on my right hand. I don’t know what happened to my mom’s.

Excited now, I wanted to scan more and more images as fast as I could. I began to formulate a plan. I’d have to buy a separate hard drive since the first scan was already a huge file size and multiplied by thousands more…yeah…new hard drive. I’d also have to mark off which ones I did and be prepared to only scan a few from each month because it was going to take a very long time even if I just did that. So lots of careful organization was going to be needed, too. I really need to plan this all out.

I chose a few more negatives to scan. One image was a portrait of my parents on the front lawn of their home in Nanuet, NY (still 1966). We must have moved there not too long before the photo was taken. My mother’s hairstyle is helmet-shaped. My dad is standing stiffly in his drab suit. They are smiling for the camera, but their eyes are not smiling. The photo doesn’t tell me how they were feeling or what they were thinking.

©1966 Feminella Family. Judith and Joseph Feminella, aka my parents.

I fast-forward in my mind, knowing what will become of them. How they will fall out of love. How my mother will want a divorce by 1986. How just before she leaves my father, she has a stroke. How she never would be free of him, of us. How he would take his life in 1999. How she would die alone in 2006.

But in the moment that photo was taken they still had over 30 years to right that ship and have a different ending. I wish I could have warned them. I wish I could have helped them make better choices. It makes me heartsick. I wonder about my own life, my own choices. I wonder what my future self would want to tell me about how I live today.

Then the scanner connection suddenly died. I turned it off, waited, turned it on again. The software kept crashing. The scanner is old and worn out. I wonder if it’s for the best that I have to stop after only scanning a few images.

The next day I try again. I’m able to scan only 4 images before the scanner fails again, but one of the images is a treasure. It shows my entire family circa 1966. It’s a very rare image that depicts both sides of our family-the Italian/Austrian side and the Russian Ashkenazi Jewish side. Back then it was not acceptable for these two cultures to intermingle. There was always an uncomfortable split between the sides of the family because of it, growing worse over the years.

©1966 Feminella Family. Christmas with my dad’s side of the family (left) and my mom’s (right).

But I get to see them again. That’s what matters now. In that moment, captured 54 years ago, we were a family. Now there’s proof. We were all smiling and happy, maybe as happy as we could be in that awkward setting. Seeing the image comforts me and leaves me anxious and greedy for more. It’s as if I saw enough photographs, the images would blow the dust off my memories, and make me whole again.

I’ll never know the truth of my family by looking at photos, but I can choose how I feel about them. I can feel haunted and desperate or I can remember the love and joy that too often fell between the frames. There are no photos of me making my mother laugh so hard she fell backward in her chair, then hit her head on the dishwasher (she was mostly unscathed), or of my father and I as we sat on the ugly brown suede modular sofa, while Johnny Carson was on the TV in the background, during one of our heart-to-heart conversations about life.

The photos are the last traces of the people I loved and one day all that will be known of me will be what is seen in photographs, too.